Wired recently ran yet another groundbreaking article (they are really good at it), that got the heads of car drivers, technology enthusiasts, and cybersecurity experts turned in the already familiar direction of car hacking. We have just gotten used to the fact that computers are hacked remotely. Now, so are cars.

No direct contact

The main subjects of the article are familiar: Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek. These extraordinary gentlemen have made names for themselves in car hacking research.

For years, they studied cars’ on-board systems, discovered the vulnerabilities therein, and demonstrated the possibility of malicious exploitation. They have previously shown how to “pwn” the car and kill its brakes using the direct access to the on-board system (i.e. having a laptop hooked up the dashboard). While dangerous, this was impractical – which carmakers were quick to point out. However, this already hinted on the very real possibility of car hacking.

Now they have shown how to “kill a Jeep” (strictly remotely), which is a big and dreary news.

Hacking my car, remotely this time #criticalsecurity

Tweet

Wired’s Andy Greenberg described the ordeal he willingly went through, quite illustriously:

“…Though I hadn’t touched the dashboard, the vents in the Jeep Cherokee started blasting cold air at the maximum setting, chilling the sweat on my back through the in-seat climate control system. Next the radio switched to the local hip hop station and began blaring Skee-lo at full volume. I spun the control knob left and hit the power button, to no avail. Then the windshield wipers turned on, and wiper fluid blurred the glass.

As I tried to cope with all this, a picture of the two hackers performing these stunts appeared on the car’s digital display: Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek, wearing their trademark track suits.

He goes on to state that Mr. Miller and Mr. Valasek developed a zero-day exploit that can target Jeep Cherokees and “give the attackers wireless control, via the Internet, to any of thousands of vehicles”. He also described the code as “an automaker’s nightmare”, since it allows hackers to send commands throught the Jeep’s entertainment system “to its dashboard functions, steering, brakes, and transmission, all from a laptop that may be across the country.”

Who let the dogs in

Wait-wait-wait, what? The dashboard functions are “married” to the entertainment system with no isolation between them? Kudos for the great security approach to the manufacturer.

As for it being “an automaker’s nightmare,” it is more likely going to be the driver’s nightmare, the kind Mr. Greenberg experienced as his transmission was remotely cut down on the highway. It wasn’t a life-threatening experience, but definitely no fun at all.

The burning question, again, is how it was possible that the “secondary,” non-critical infotainment system appeared to be so closely integrated with the “primary,” absolutely life-critical dashboard functions. These systems aren’t just isolated from each other – it is really possible to do anything to the car – and all it takes from the attackers, according to Wired’s article, is to know the car’s IP address.

“All of this is possible only because Chrysler, like practically all carmakers, is doing its best to turn the modern automobile into a smartphone,” Mr. Greenberg wrote. And after what he has experienced this acrimony is understandable.

Haven’t we warned..?

Honestly, it was coming for a long while. Our boss, Eugene Kaspersky, who recently shared his thoughts on the matter (take a look), said he was “joking” about the possibility of a car hacking back in 2002. In 2015, it’s a reality.

“Some auto manufacturers keep squeezing onto CAN [controller area network – the on-board communications system that interconnects and regulates the exchange of data among the various devices] more and more controllers without considering basic rules of security. Onto one and the same bus – which has neither access control nor any other security features – they strap the entire computerized management system that controls absolutely everything. And it’s connected to the Internet,” Mr. Kaspersky wrote.

CAN was developed 30 years ago, and it has no security functions built-in. And yes, now it is connected to the Internet without any “division of trust.”

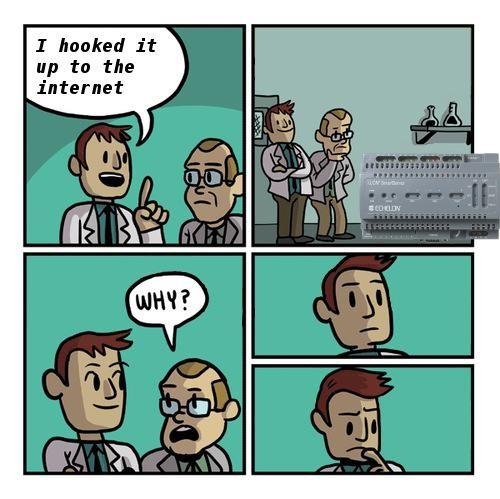

A straight-to-the-point picture:

In fact, there is an answer to this “why?” Actually two: a simple one, and a complex one.

A simple one is “marketing.” The complex one is “a consequence of a common business logic.”

This logic says: “Well, we need to stay ahead of the competitors, so let’s make this one new fancy car model even more appealing. How? Let’s stuff it with electronics and call it ‘smart.'”

And then marketing: “Hey! Have we got a deal for you – the car that is so smart it obeys your commands via a smartphone.”

And the person who bought this “smart” car: “Wow! I have a car that’s hooked up to the Internet; it’s cool!”

It becomes way less cool as soon as remote hacking becomes possible – it is a dream gift for both car thieves and much more capital offenders. After all, the primary problem is the old one: the automotive on-board system lacks the “security-by-design.”

“Throughout the auto industry there’s a tendency – still today! – to view all the computerized tech on cars as something separate, mysterious, faddy (yep!) and not really car-like, so no one high up in the industry has a genuine desire to ‘get their hands dirty’ with it; therefore, the brains applied to it are chronically insufficient to make the tech secure”, Kaspersky writes, adding that everywhere the hasty “growth of functionality of all this new tech is hurtling ahead without taking security into account!”

Yes, this is the case with other critical infrastructure – and cars can easily be called “critical infrastructure” too: Lives depend on how safe they and their CANs are.

And it is wrong to say that a modern car’s on-board systems are reliable on their own, even without added internet connectivity. They are not.

Recently, a fellow alumnus of this post’s author, a well-known business journalist, barely survived a serious accident: An airbag did not deploy despite the fact that the driver was buckled up properly and the hit was frontal.

The car manufacturer’s support service said that the on-board system decides whether to open the airbag based on a number of various factors in order to minimize the possible harm (in some situations airbags may inflict extra injury on the driver). And in this particular case, it decided that airbag should not be opened. That really looks like a malfunction, and… Well, “the system decided not to open the airbag” sounds wicked, does it not?

An exploit let the hackers to take over all of the car’s systems remotely #criticalsecurity

Tweet

An acknowledged problem

Automakers acknowledge there is a problem, and apparently, so do legislators. Wired’s Andy Greenberg wrote that Miller and Valasek managed to “spook” the industry and “inspire” legislation: A new bill that’s designed to require cars to meet certain standards of protection against digital attacks and privacy is underway in the U.S., and hopefully other nations will follow suit.

The entire automotive industry is on its toes. US Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers announced the creation of an Information Sharing and Analysis Center to deal with cyber threats and vulnerabilities in the on-board electronics and in-vehicle networks.

It’s up to the manufacturers to change the approach to designing modern hi-tech equipment. As we have written before, security should come first. It must be taken in account at the design level, not added later (if added at all). It is the only way to decrease the risk level – both for automotive systems and other civilian critical infrastructure – which is high enough without an unnecessary exposure to cyberthreats such as in the case of a remotely hacked Jeep.

car hacking

car hacking

Tips

Tips